DESIGNING A CEMETERY IN LAND-SCARCE SINGAPORE

An architect reflects on how designing a cemetery has

helped him in his bereavement after his own father’s passing

SJ Architecture

February 2023

Choa Chu Kang Cemetery site, the only burial ground in Singapore

Abstract: The writer was an intern when he helped design space in a crematorium in

Singapore, a project that he subsequently used during his own father’s cremation. This

began an enduring interest in the design of after-death facilities, culminating in his work on the Choa

Chu Kang Cemetery, the only cemetery in land-scarce Singapore, a country with a greying population. He

discusses how the authorities use a prefabricated crypt building system with removable covers to facilitate

the “reuse” of crypts, offering an insightful look at the sensitive manner in which death and burial are

handed in a multi-religious society.

Reflections beyond the drafting board

When I started my architectural internship in 2003, one of my first tasks was to help with the drafting for

the furniture, fittings and spaces within a crematorium development in Mandai, in the northern part of

Singapore.

I remembered my mentor speaking about the design of the spaces and the furniture from the point of view of the users – the next-of-kin, how the seats would have tall backrests to serve as privacy screens, for the next-of-kin to have a moment of private silence after coming out of the viewing gallery.

As fate would have it, when my father passed away two years later, the cremation was held in the same crematorium that I had helped in the drafting.

That was the first of many experiences I had at the crematorium, as I encountered more deaths among my extended family and friends. The same emotions would still come rushing every time in the viewing gallery, watching the casket slowly move through the courtyard into the furnace. The body, no, the person that I had known, would be no more, reduced to ashes. That was the final moment, when grieving transitions into the process of acceptance.

Death as a natural part of life

I used to be afraid of passing through cemeteries or walking past wakes being held on the ground

floor of Singapore’s public housing blocks.

My experiences of the death of loved ones slowly changed my thinking, and I started to be interested in

funerals, and the various post-mortem rituals of different communities. I realised there are differences

between Taoist rituals for different Chinese dialect groups. I started trying to understand how

Malay-Muslim rites for the deceased were conducted, and became intrigued by the sounding of the

horn and beating of drums in Hindu funerals. I would often wonder if the person had lived to a ripe old

age and how the family members were coping, and even where his or her remains would be interred, if

he or she had chosen to be buried.

Death is often a sensitive subject, but my personal experiences – especially with losses in my family and circle

of close friends – have made me more open to discussions of death and dying.

I started to be interested in funerals, and the various post-mortem rituals of different communities. I realised there are differences between Taoist rituals for different Chinese dialect groups. I started trying to understand how Malay-Muslim rites for the deceased were conducted

As Sallie Tisdale, a nurse who made a name for herself by writing about caregiving, writes: “To accept

death is to accept that this body belongs to the world. This body is subject to all the forces in the world.

This body can be broken. This body will run down.” We come to terms with our own mortality through

accepting the demise of people close to us, as we go through the process of cremation or burial of our

loved ones. The finality of the ritual also reminds us of the ephemeral nature of life.

Bereavement in Singapore

Living in a densely populated and greying society like Singapore, one inevitably confronts the reality of

death frequently, from funerals and last rites held at housing blocks to the hearses and processions we

see on roads. These rituals help to bring a sense of closure, to help the living deal with the demise of their

loved ones.

As a multi-cultural society, providing for different racial and religious groups and their requirements for

bereavement arrangements is important. Paradoxically, wakes and processions are often social affairs

at the same time, as families gather to mourn, undergo the rituals of bereavement, which can be rather

complex sometimes. It is at the moment of cremation or burial that we have a chance to say our final goodbye.

One of the first things I learnt is the amount of care and thinking that goes behind the planning and

provision of after-death facilities in Singapore.

In a land-scarce, multi-religious and multi-racial society like Singapore, there is a lot of sensitivity for the religious burial needs within tight land constraints. Although cremation is popular, the country accepts that burial remains a preference for some, and even mandatory for some religious groups.

An example is the New Burial Policy, introduced in 1998 to address the issue of land scarcity. The New Burial Policy limits burial to 15 years. After this period, graves will be exhumed and the remains cremated or re-interred, depending on one’s religious requirements.

In a land-scarce, multi-religious and multi-racial society like Singapore, there is a lot of sensitivity for the religious burial needs within tight land constraints. Although cremation is popular, the country accepts that burial remains a preference for some, and even mandatory for some religious groups.

Working on Choa Chu Kang Cemetery

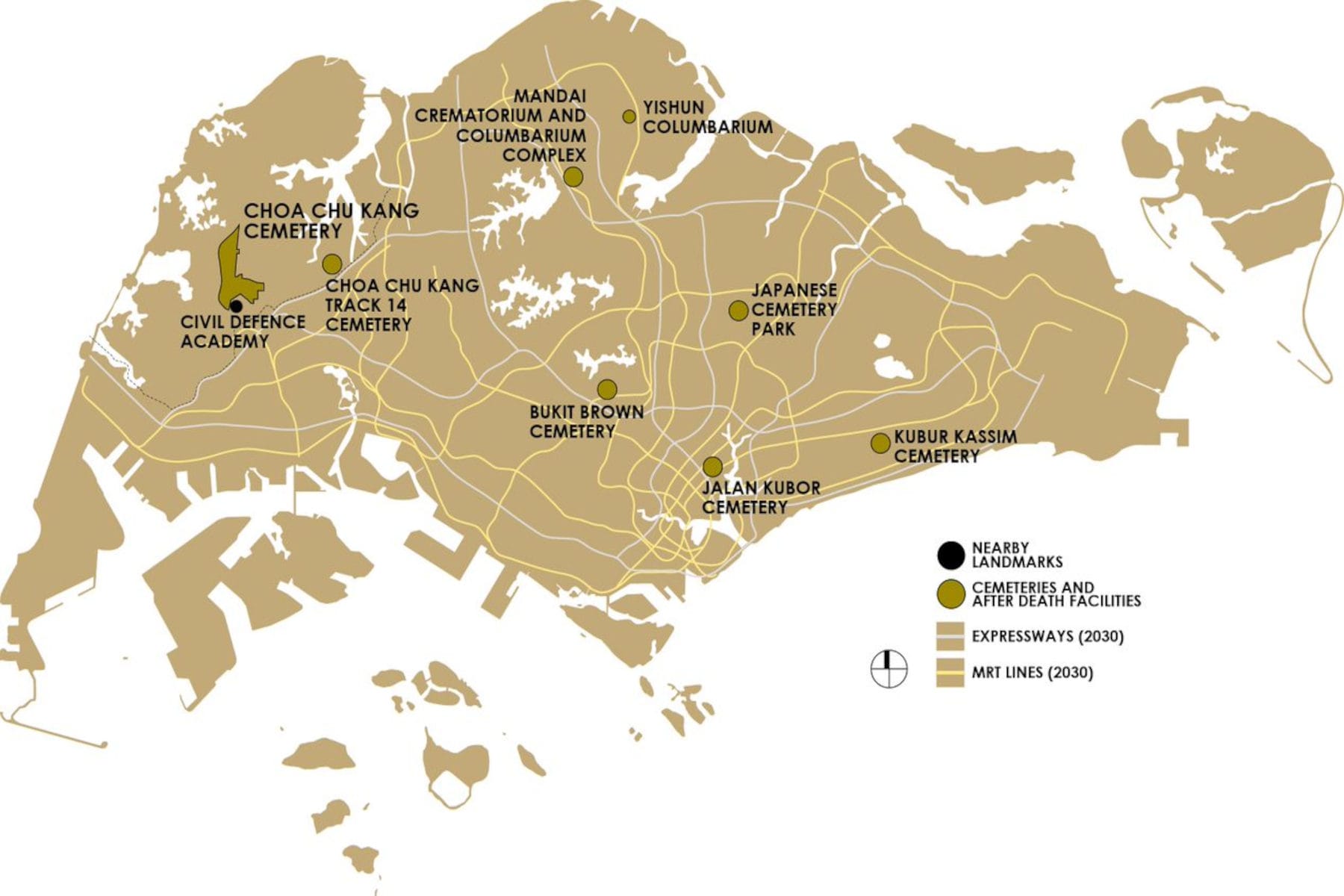

Choa Chu Kang Cemetery, located in the north-western part of Singapore, is the only burial ground in

Singapore. All other cemeteries, including Bukit Brown Cemetery, Jalan Kubor Cemetery, Japanese

Cemetery Park and Kubur Kassim Cemetery, were closed over the last century.

Many of the former cemeteries were also exhumed and redeveloped over time, such as Pek San Teng

which is now Bishan North, a housing estate. Another cemetery, Bidadari Cemetery, is now being

developed by the Singapore housing authority into a residential neigbourhood, while Gali Batu Cemetery

was redeveloped into a depot for the Downtown MRT Line.

Location of cemeteries and public after-death facilities in Singapore(Graphic: SJ Architecture)

Memorial spaces for those we love

Surbana Jurong Consultants Pte Ltd, was given the opportunity to plan, design and

manage the implementation of burial facilities in Choa Chu Kang Cemetery under a multi-disciplinary

consultancy project with National Environment Agency (NEA) in 2016. It was an eye-opening

experience for the team, as we often visited Choa Chu Kang Cemetery for studies, site meetings and

inspections.

Walking through the burial grounds and maintaining a general respect to the graves became a weekly

affair for us. During my site studies for the preparation of master plans for the cemetery, I would often

stroll alone across the vast cemetery area in the morning, soaking in the nature and serenity.

As part of the New Burial Policy, the Crypt Burial System (CBS) was introduced by the authorities from

2007. This was a very important improvement for the way individual graves were demarcated.

Previously, the boundaries for individual graves were marked on the ground for excavation by burial

workers before burial. This was time-consuming, labour-intensive, and unsustainable for a fast ageing

population. Another disadvantage was that there had to be sufficient buffer space between graves to

allow for working space during excavation.

The CBS solved these problems, simply by having burial crypts fashioned out of prefabricated

reinforced concrete structures without a base, with features that are designed to meet the burial

requirements for various religious groups.

The crypts are only filled with earth after the burial rites are completed, cutting down the time and

labour required to excavate the graves manually. The CBS also has removable crypt covers, which

allow the graves to be easily exhumed after 15 years, so that the crypts can be re-used.

A view of the crypt Burial System used in Choa Chu Kang Cemetery

In the Choa Chu Kang Cemetery, there are areas with burial crypts for Muslims, Taoists, Christians and Hindus. The Christian Cemetery is further demarcated into Roman

Catholic and Protestant Divisions, and also features Lawn Cemeteries.

The vast majority of the crypts built using the crypt

burial system are within the Muslim Cemetery. Crypts

were built with the longer side facing Mecca, such

that the body would be laid slightly on the side, and

with the face turned towards Mecca. Some crypts

were also built for reinterred remains which were

exhumed from the fresh burial crypts after 15 years.

These crypts would be used to re-inter the remains of

between eight and sixteen individuals that had been

exhumed and wrapped. Some of these crypts were

also used for the burial of the surgical remains of Muslim

individuals, which may include limbs and organs, as

well as foetuses of the stillborn. (More information on

the exhumation and reinterment process may be

found in Wareesan Management’s website.)

While

preparing the master plan, we learnt about some

unique requirements for other religious groups, and we applied these to

our plans for the Jewish Cemetery, Baháʼí Cemetery

and Parsi Cemetery within Choa Chu Kang

Cemetery.

A view of the Lawn Cemetery at Choa Chu Kang cemetery

The CBS solved these problems, simply by having burial crypts fashioned out of prefabricated reinforced concrete structures without a base, with features that are designed to meet the burial requirements for various religious groups.

We have also come across interesting ways some cities resolve the issue of lack of burial space.

These includes vertical cemeteries, where large niches for full burial are stacked in high-rise buildings.

Some examples include the Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica in Santos, Brazil, and Yarkon Cemetery

near Tel Aviv, Israel.

In Singapore, good urban planning has ensured that sufficient land is secured for cemeteries. The

Choa Chu Kang Cemetery is located within the Western Water Catchment. Its hilly terrain makes it

suited for other types of land use. Due to the undulating terrain, we often need to terrace sections of

crypts to mitigate the level difference, which bears some resemblance to “The Grid Meets the Hills” in

some cities, where we had to use a series of ramps and staircases to maintain accessibility.

This brings unexpected results sometimes, such as a “green tunnel” gateway promenade in the

Christian Cemetery, or a pavilion with the best view in the Chinese Cemetery.

Green Tunnel Promenade

Other than the crypts, and roads and footpaths, we have also designed the pavilions within the cemetery, which was planned to allow each pavilion to be within one-minute walk from anywhere within the cemetery grounds, to provide shelter for visitors from weather conditions.

These pavilions are kept open to capitalise on the views to the surrounding greenery, offering a sense

of calm and a reminder of the cyclical nature of life for the visitors.

Another feature that NEA provided within the Choa Chu Kang Cemetery is the new Garden of Peace. The serene garden is designed as an open garden designed for the scattering of cremated ashes in a respectful and dignified manner. It was built in response to a growing interest by Singaporeans to have the cremated

remains of their loved ones returned to nature.

Space for the living to remember

One of the pavilions in Choa Chu Kang Cemetery

We wanted to focus on the living as much as the departed, and designed these spaces for the

next-of-kin who are grieving, or returning to the cemetery to visit the graves during significant

anniversaries of their loved ones or during festivals such as Qing Ming, All Souls Day and Hari Raya

Haji.

Seats are clustered around the columns to allow the next-of-kin to engage in private conversations, and

the pavilions are surrounded with flowering shrubs and small trees to provide shade and added weather

protection. The pavilions also act as intimate spaces that contrasts with the openness of the cemetery

grounds, as a space for reflection and comfort.

Greenery in the Cemetery

In many of the songs and rites conducted during

funerals rites, regardless of culture and traditions,

there is often a theme on the cyclical nature of time

and the seasons, and by extension the cycle of life.

The physical manifestation of this theme can be

observed in the cemetery, from the seasonal birds

chirping and flying between the trees, to the

colourful whirligigs spinning away on the graves in

the wind. We try to capitalise on these elements of

nature by introducing trees with low canopies closer

to the ground, which rustle in the wind and provide

shade for visitors.

Throughout the entire period of the construction, most of the site supervision staff and contractor

management team told us that they liked working in the environment in Choa Chu Kang Cemetery.

Indeed, we found the cemetery very calm, peaceful, and therapeutic to the mind and soul. Perhaps it is

the constant reminder of one’s own mortality, or the endless greenery, the landscaping with the variety

of young and mature trees, with the periodic blooming of the trumpet trees.

It is perhaps the environment that draws me to take walks within Choa Chu Kang Cemetery often, be it

on days for regular site walks and meetings, or as part of my research on the area to prepare for concept

studies and reports.

I feel privileged to have been able to plan the cemetery as I take these walks, knowing that death is a

natural part of life, and reflecting on those who have departed, and the part of our lives that we have

shared.

Trumpet Trees Blooming in the Cemetery

Project

Redevelopment of Choa Chu Kang Cemetery

Location

Jalan Bahar, Lim Chu Kang Road, Old Choa Chu Kang Road – Western Catchment

Area, Singapore

Size

250 ha (overall land area)

Status

250 ha (overall land area)

Ongoing (Last development phase)

Ongoing (Last development phase)

Client

National Environment Agency

Services

Full Suite Multi-Disciplinary Consultancy (Arch, C&S, M&E, QS)

Firm / BU

SJ Architecture, Team 7

Collaboration

No external consultants

Project Lead

Liew You San (Project Director)

Du Peng (Project Lead / SO Rep – First 2 development phases)

Koh Wei Kiang (Planning and Project Lead – All phases and Masterplan / SO Rep – Last 2 development phases)

Du Peng (Project Lead / SO Rep – First 2 development phases)

Koh Wei Kiang (Planning and Project Lead – All phases and Masterplan / SO Rep – Last 2 development phases)

Project Team

Bonifacio JR Dorado Honrado, Huszairy bin Mohd Zamry, Gementiza Jefferson Paul

Canonigo, Hoo Lee Choo, Lu Pengzhou (Landscape Architect), Derrick Zong, Liu

Yunpeng, Justin Pang (C&S Engineer), Lim Teck Chye (Electrical Engineer), Ellen Lai,

Richard Chung (QS)

Keywords

Cemetery, Burial, After Death, Crypts, Funerary Cultures and Practices, Precast

Construction.

The SEEDS Journal, started by the architectural teams across the Surbana Jurong Group in Feb 2021, is a platform for sharing their perspectives on all things architectural. SEEDS epitomises the desire of the Surbana Jurong Group to Enrich, Engage, Discover and Share ideas among the Group’s architects in 40 countries, covering North Asia, ASEAN, Middle East, Australia and New Zealand, the Pacific region, the United States and Canada.

Articles at a glance