HOW CAN HEALTHCARE DESIGN SUPPORT INDIVIDUAL WELLNESS?

Architect-turned-full-time mother

Sok Leng has three children, with the eldest being a special needs child with severe and multiple disabilities. She is familiar with the hospital setting and often finds herself having to make difficult decisions in a clinical environment

Architect-turned-full-time mother

Sok Leng has three children, with the eldest being a special needs child with severe and multiple disabilities. She is familiar with the hospital setting and often finds herself having to make difficult decisions in a clinical environment

Due to a sporting accident in 2021, Linda underwent a few months of surgical and post-surgical rehabilitative care and convalescence for back and leg surgery. She stayed variously in a high dependency ward, inpatient ward and rehabilitation ward. This has impacted her understanding of how the healthcare environment affects the recovery process.

Architect at SAA Architects Received some months of surgical and post-surgical rehabilitative care and convalescence

Due to a sporting accident in 2021, Linda underwent a few months of surgical and post-surgical rehabilitative care and convalescence for back and leg surgery. She stayed variously in a high dependency ward, inpatient ward and rehabilitation ward. This has impacted her understanding of how the healthcare environment affects the recovery process.

Linda Lee Wen-Xin

Architect at SAA Architects

Received some months of surgical and post-surgical rehabilitative care and convalescence

Co-founder of STUCK, a design and innovation consultancy

Yong Jieyu is a multi-disciplinary designer and co-founder of STUCK. His recent works investigate the use of design thinking in the design of future spaces. His projects include nursing homes, assisted living facilities, hospitals and healthcare programmes.

Yong Jieyu

Co-founder of STUCK, a design and innovation

consultancy

Yong Jieyu is a multi-disciplinary designer and co-founder of STUCK. His recent works investigate the use of design thinking in the design of future spaces. His projects include nursing homes, assisted living facilities, hospitals and healthcare programmes.

“How can HEALTHCARE designERS give paediatric patients more emotional support?”

- Caregivers need spaces that give them emotional support as they process critical conversations with doctors and nurses.

- Paediatric patients need to be protected from the tense and hectic environments of ERs and ICUs.

- Spatial designs that offer a sense of “uplift” provide a sense of hope.

- Offering choice, even in the final months, give patients and caregivers a sense of independence and dignity.

Tan Sok Leng

Architect-turned-full-time mother of a special needs child

Being overwhelmed in a hectic healthcare setting

It is rather surprising and contradicting to see many happenings taking place within an ICU waiting area, where patients and their families experience higher levels of anxiety.

Another good example is the Early Intervention Centre (EIC) at Rainbow Centre Margaret Drive Campus.

Sok Leng visited Rainbow Centre’s Early Intervention Centre (EIC) on the recommendation of an architecture friend. On her first visit to the new extension, she noticed “interesting light shafts” coming into the main lobby space, which functioned as an internal play area and an out-of-classroom rehabilitative therapy area. Within the interiors, they had intentionally done away with the traditional classroom model so that these children have more interaction. These zones of spaces were all facing a large green open space at the back, separated by full height glass doors that opened into a nice verandah area for water play for the children. The sun shading façade of the verandah also brought in a delightful play of light and shadow for the children.

(Above) The main lobby space, which also doubles up as an internal play area. (Photo: Rainbow Centre Margaret Drive Campus)

Can healthcare learn from deathcare?

Being able to advocate the care we wish for our loved ones, including the process leading to death is one way to bridge the divide between life and death.

Architect, SAA Architects

“How can WE create spaces for people to recover from severe injuries and protect their SHATTERED self-ESTEEM?”

- Universal Design helps patients who are suddenly incapacitated to learn to use mobility aids to regain their sense of self.

- Patients need valuable space in hospitals to learn how to use wheelchairs and other tools to help them with daily activities in their own homes.

- Access to windows, natural light and greenery helps patients to recover.

- Designing spaces for a transition to deathcare can give dying patients a sense of dignity and closure.

Using Universal Design for every stage of recovery

Using Universal Design for every stage of recovery

The emotional boost with greater mobility and the desire to uphold our sense of self-independence and self-esteem cannot be underestimated.

Close interaction with patients to help them regain independence

There needs to be sufficient space in the rehabilitation ward to allow these simulations to be carried out to boost the confidence of the patient.

The importance of windows and light

Transition to deathcare: addressing the specific needs of users

The term “user” goes beyond just patient’s needs but also the many caregivers and even visitors who themselves are in a state of transition while their loved ones are hospitalised.

“We need a mindset shift to Design for ageing and dignity in death”

- The process requires designers to listen first before creating

- Challenges such as nimbyism and a bureaucratic mindset to building facilities need to be overcomed

Co-founder of STUCK, a design and innovation consultancy

Yong Jieyu is a multi-disciplinary designer and co-founder of STUCK. His recent works investigate the use of design thinking in the design of future spaces with notable projects in healthcare: nursing homes, assisted living, hospitals and healthcare programmes.

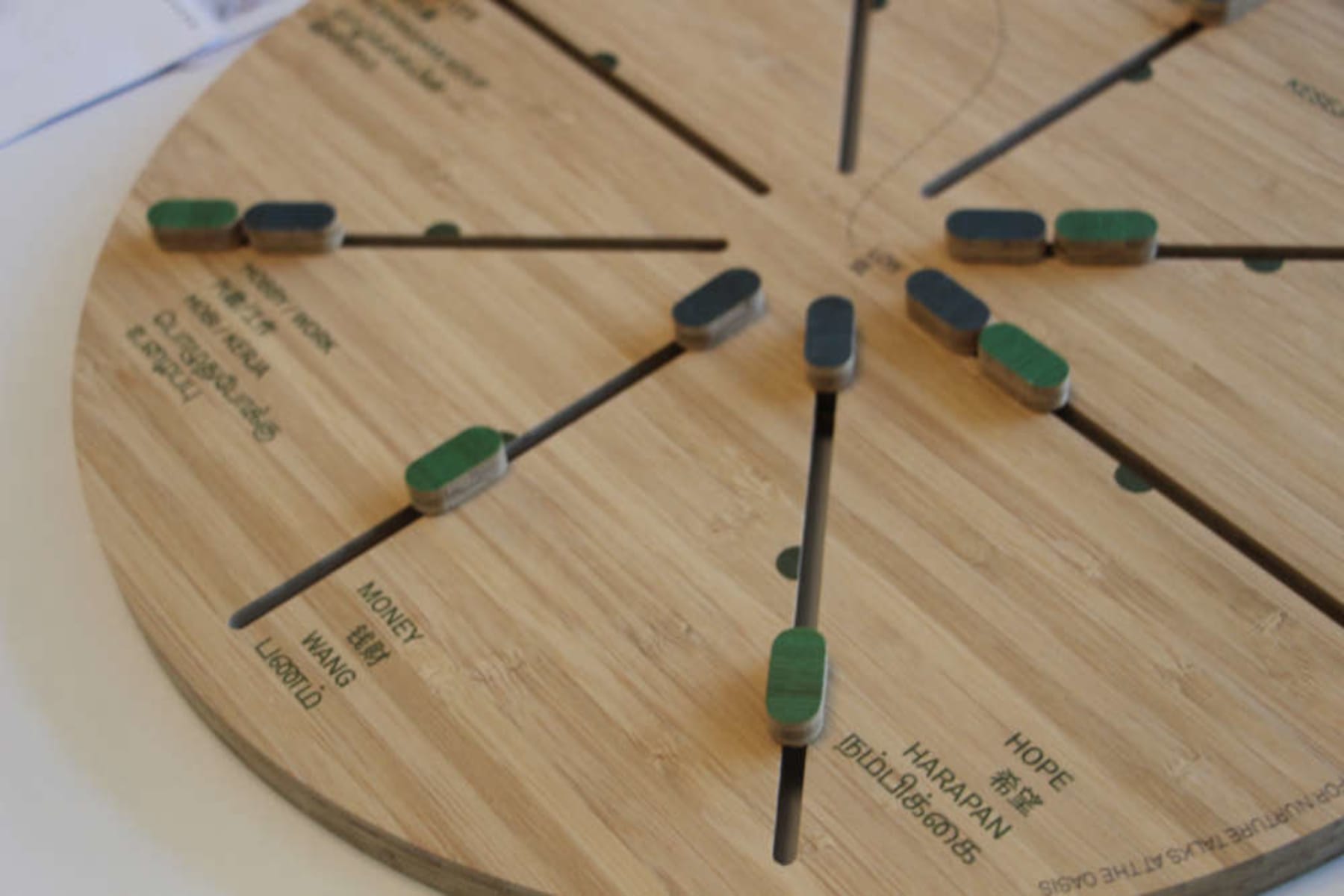

Designing for good means listening first

It is impossible for the design team to have fully experienced or understood the needs of the healthcare system users.

Balancing a person-centred model with operational efficiency

Innovative ideas would typically require changes in mindsets among stakeholders in the built environment and tweaks to healthcare operations.

Mindset shifts for managing deathcare

“We as a society need to understand it is normal to age, and that perhaps, talking about ageing and dying is beneficial to the individual and the family.”

Articles at a glance