THE GLARING CONTRAST

During my research, I found that a major part of our problem as a species is that years of technical advancements have separated us from the rest of the natural world. Unlike any other species on the planet, we’ve been able to harness stored energy through fire to build new materials and to re-engineer vast environments to where we are today – two contrasting worlds in stark opposition to each other. Grey versus green. Grids versus gradients. Engineered versus emergent. We have built ourselves outside of nature, in what metallurgist, Ursula Franklin, calls a “house of technology”. A house that we are seemingly so preoccupied with expanding that we’ve neglected the importance, and the potential, of the natural world that surrounds it.

Underlying this division is really about how we think of ourselves and the assumptions we use to design. For example, for centuries we have been designing under the assumption that humans are somehow separate from nature, that we can control her, or that nature exists purely for human consumption. And although these assumptions have helped us become a dominant species; we now see that they are currently outdated.

For years, we have been successful in creating stable environments for ourselves under these assumptions. But as we sneak further into more forests, pave over wetlands, and engineer more streams, we are attempting to suppress an insuppressible system and adding to a very precarious contrast. We are disrupting the ecosystems that support our lives and adding to the instability of our planet. As we all know, nature feeds our bodies, communities, economies, and infrastructure. Nature helps regulate the planet. But as we expand under these outdated assumptions, we build a gradient that nature is attempting to fight against. Nature abhors gradients, which is why it’s always less expensive to find ways to work with her, than against her. Consider a thought experiment; what would happen if we all left the cities today? Nature would take over. This is because, as I said, nature wants to blend, dissipate, and strive for equilibrium. So, the more we build on this house of technology, the more we are unnecessarily using energy and materials to try to resist this gradient, and the more we do, the more expensive it becomes and the larger for potential failure.

The interesting contradiction in this is that in our attempt to create stable environments by engineering nature out of our cities, we are inadvertently adding instability at a global scale. So, how do we reconcile this?

My suggestion is that we learn to listen a little more closely again, and let nature lead our designs.

The Living Story

Our biomimetic Master Plan of the Living Story

In every case, the Living Story inspires us to go beyond the idea of “doing less harm” to actively design regeneratively because it is rooted in the belief that if our breath feeds trees and our bodies feed our soil, why can’t our buildings feed their ecosystems?

In essence, the Living Story is a conversation. It is learning the brush strokes of a place, of a masterpiece, so that we can more effectively add to it. This includes learning the subtle nuances of what nature has done, is doing, and will do, so that we can more strategically place our infrastructure within it, in a way that contributes. Or, it could be leveraging the existing services that nature already provides, like carbon sequestration, water retention, storm dissipation, food production and pollination, purifying water and air or controlling temperature. In every case, the Living Story inspires us to go beyond the idea of “doing less harm” to actively design regeneratively because it is rooted in the belief that if our breath feeds trees and our bodies feed our soil, why can’t our buildings feed their ecosystems?

The following are examples of how we are exploring this within the SJ Group.

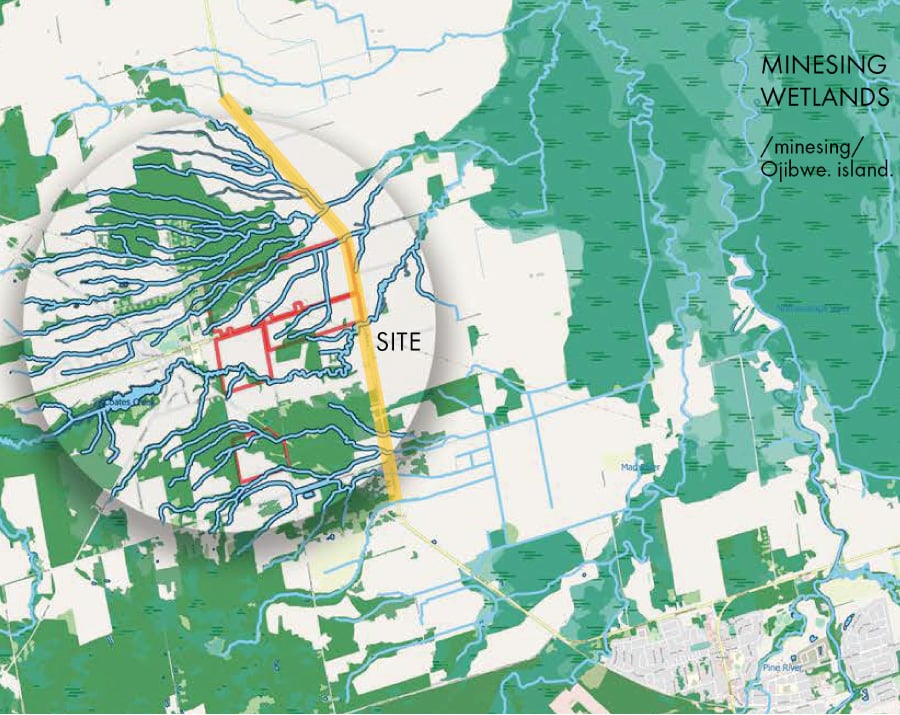

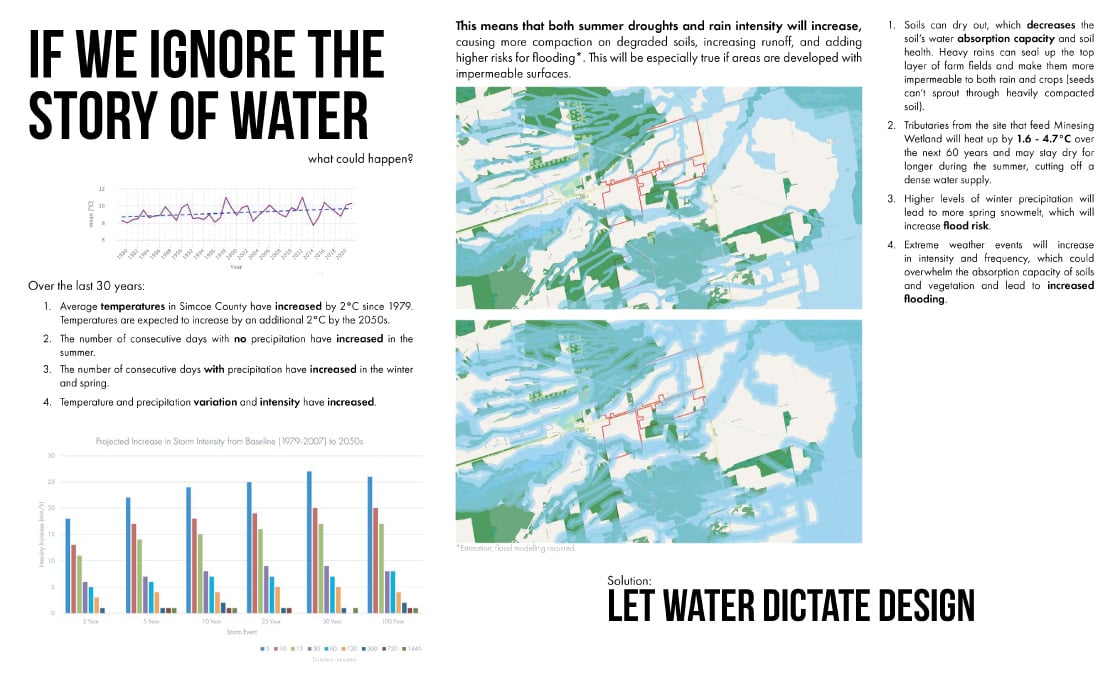

Case Study 1: What the land wants to do

In a 200-ha development in Ontario, Canada we learned that the buried and ephemeral ditches that ran through the property were connected to a much larger, and provincially significant wetland. We learnt that roads and tile beds in the agricultural fields have severed this connection. We learnt that with climate change projections, these ditches are potential flood zones, despite seeming completely inert. This then helped us form a vision, the principles, and the framework for our vision plan for the client. A plan that was dictated by what the land wanted to do, rather than what we wanted to engineer the land to do. We saw the existing ditches as opportunities rather than features that needed to be filled in.

A plan that was dictated by what the land wanted to do, rather than what we wanted to engineer the land to do.

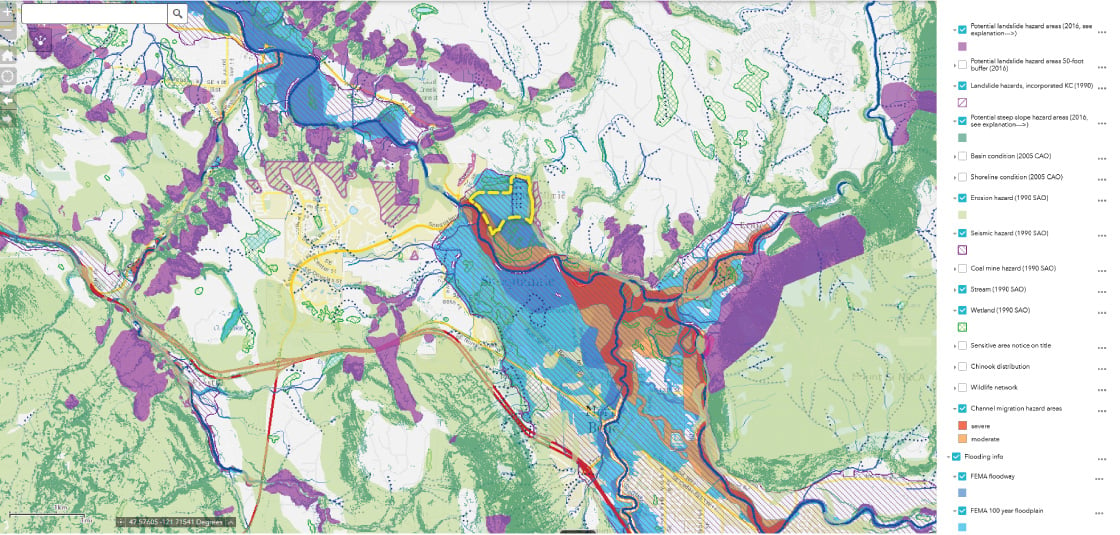

Case Study 2: What the land will permit us to do

In a project in the West Coast of the United States, the Living Story helped us map out a client’s vulnerability to multiple climate change scenarios. We found that their location in the mountains was ripe for flooding, high windstorms, and potential forest fires. Beyond that, we also learnt how the site they were exploring has deeply significant indigenous history and that not only were there environmental pressures to contend with but the potential of significant social pressures as well. This led to ways of thinking adaptively in response to future climate scenarios, including using a “patch model” of decentralised infrastructure and making sure each strategy of design was responding to the potential climate risks. It also led to indigenous engagement for a reconciliation and partnership pathway for moving forward.

Case Study 3: What the land support us in doing

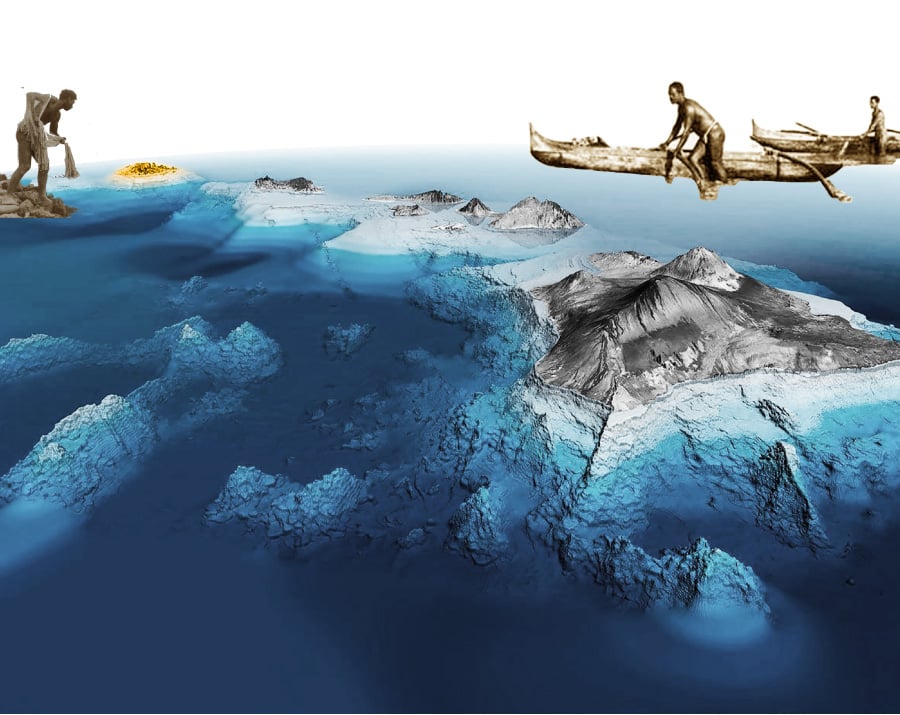

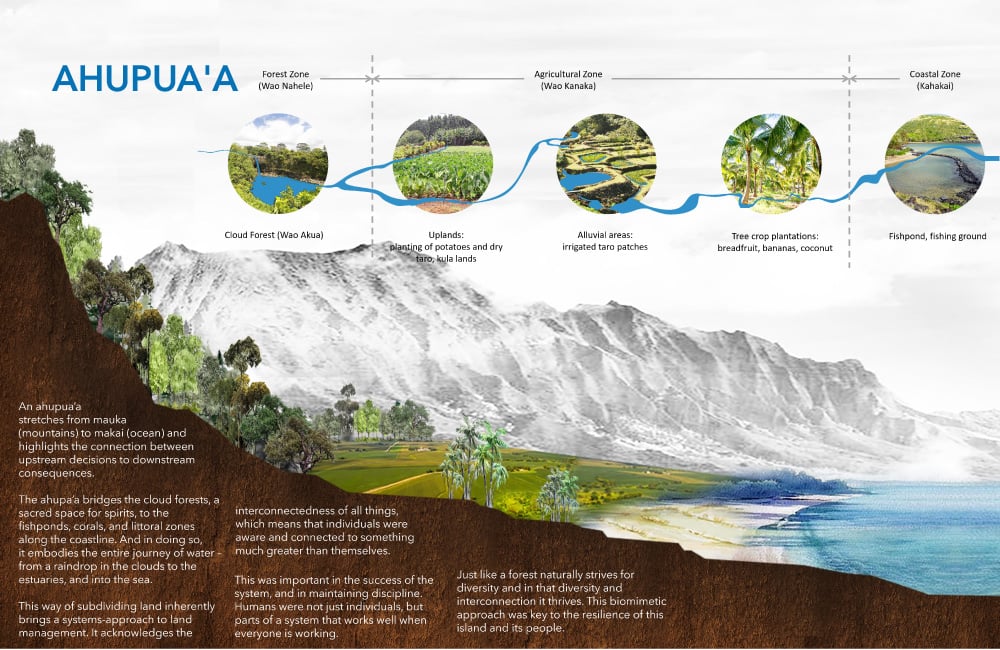

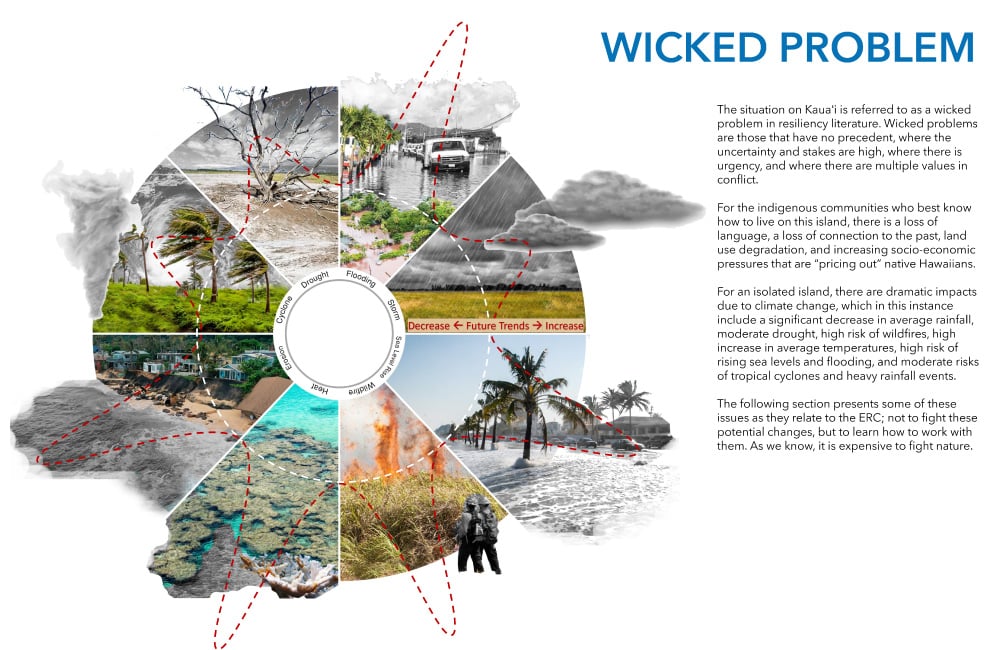

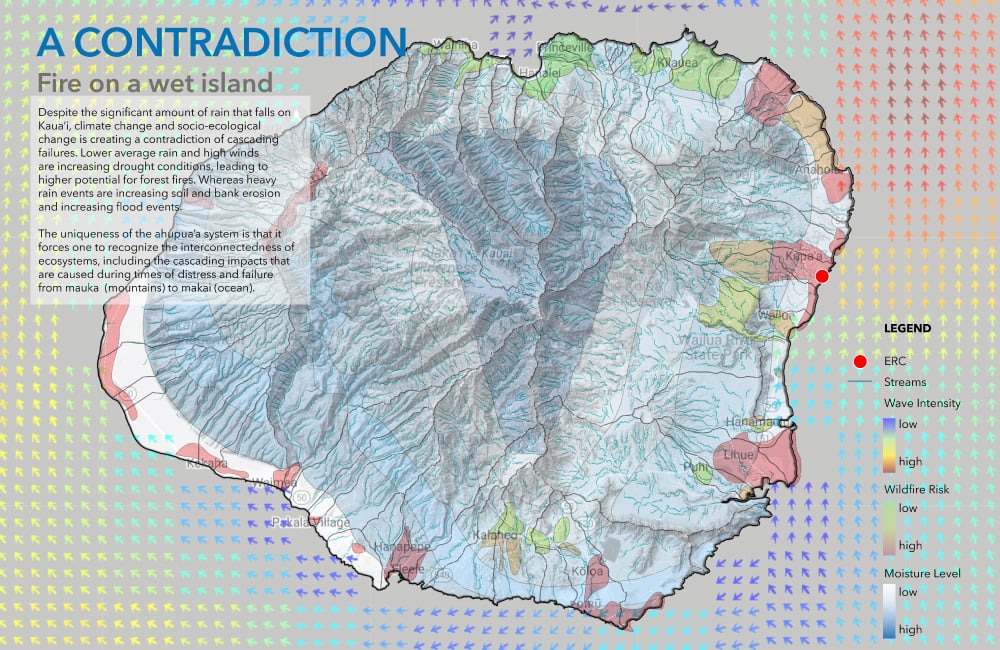

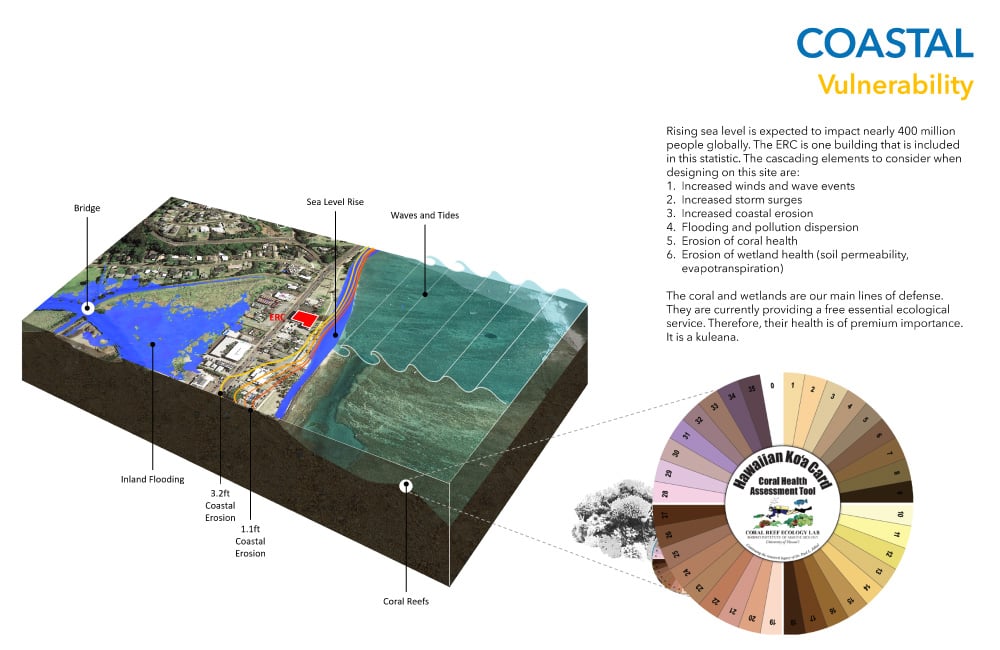

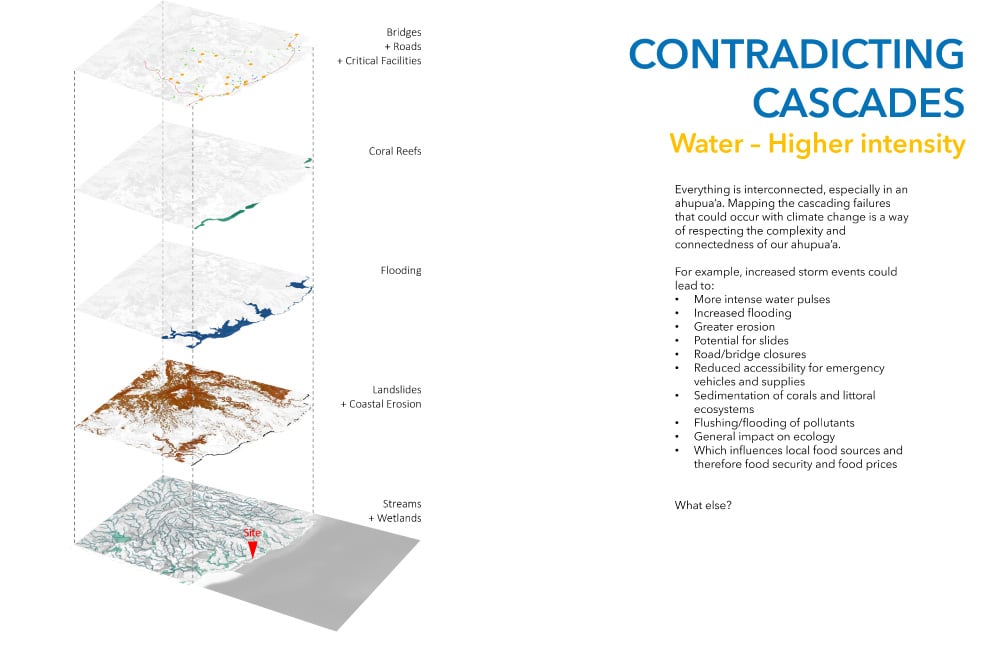

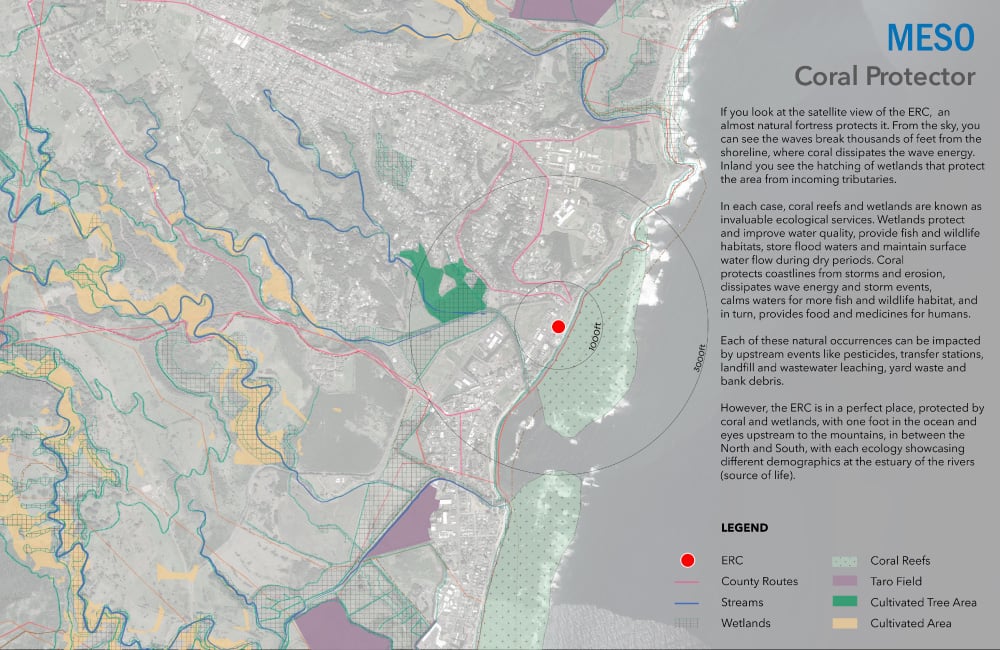

In Kaua’i, the oldest Hawaiian Island, we helped the Kaua’i Federal Credit Union design their Economic Resilience Center by first providing a Living Story assessment. Within it, we identified both climate change risks and ecological assets, but we focused our first year in a deep consultation with Indigenous Hawaiians.

Case Study 4: What the land could inspire us to do

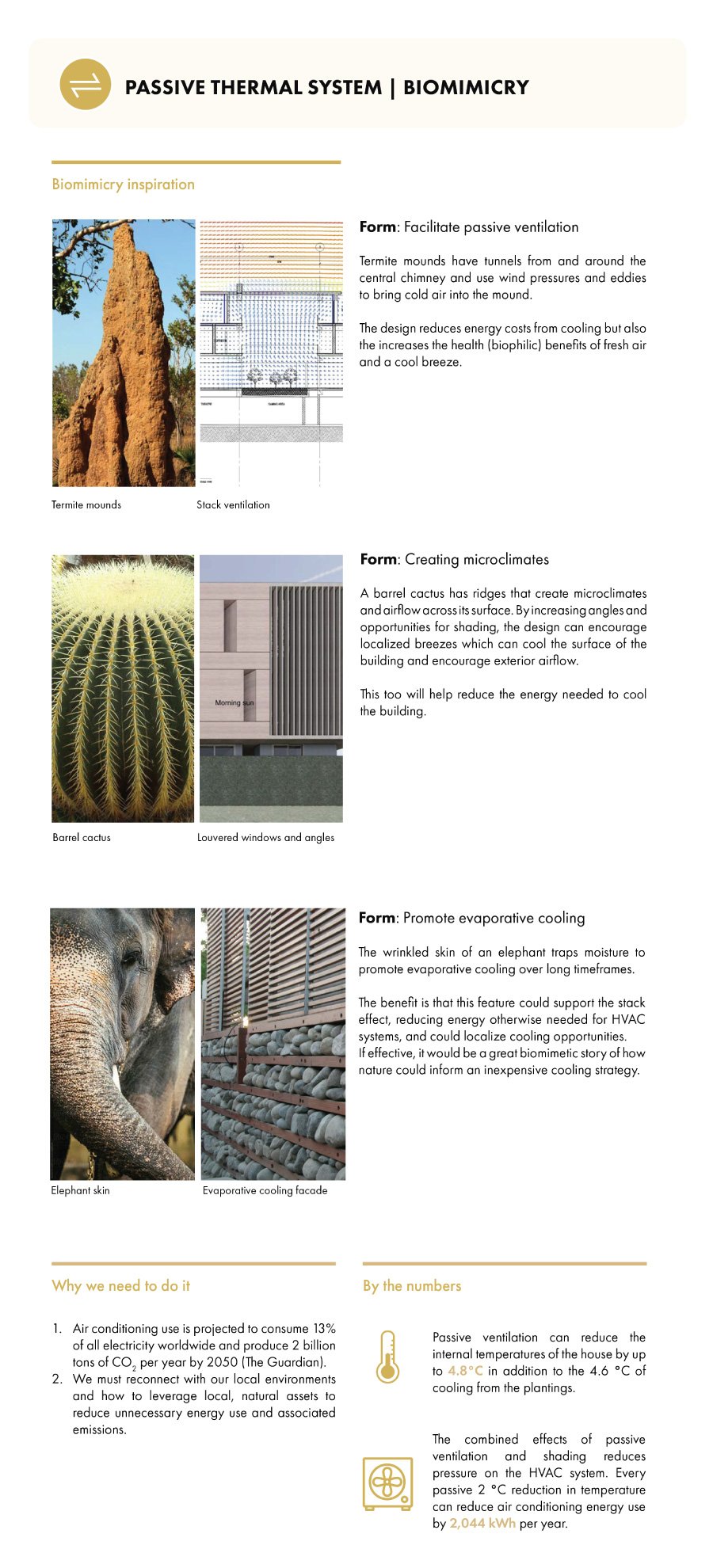

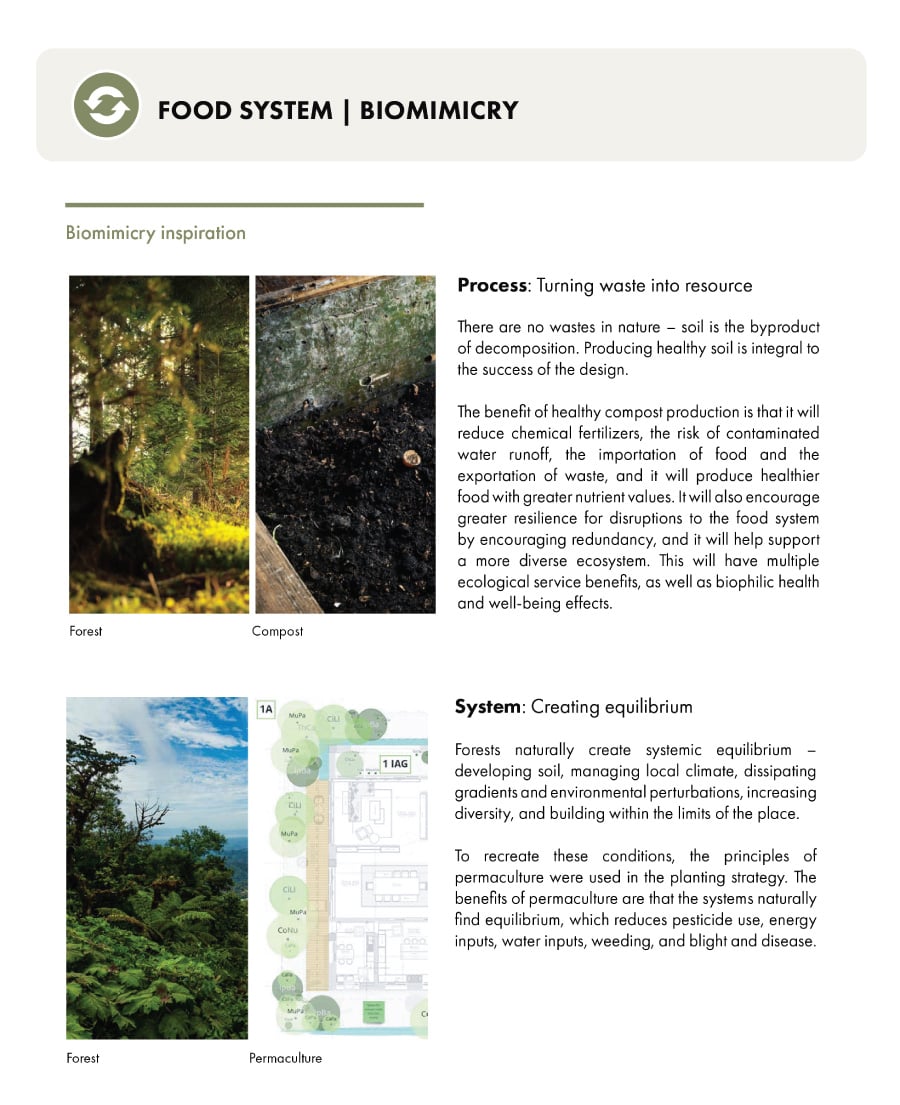

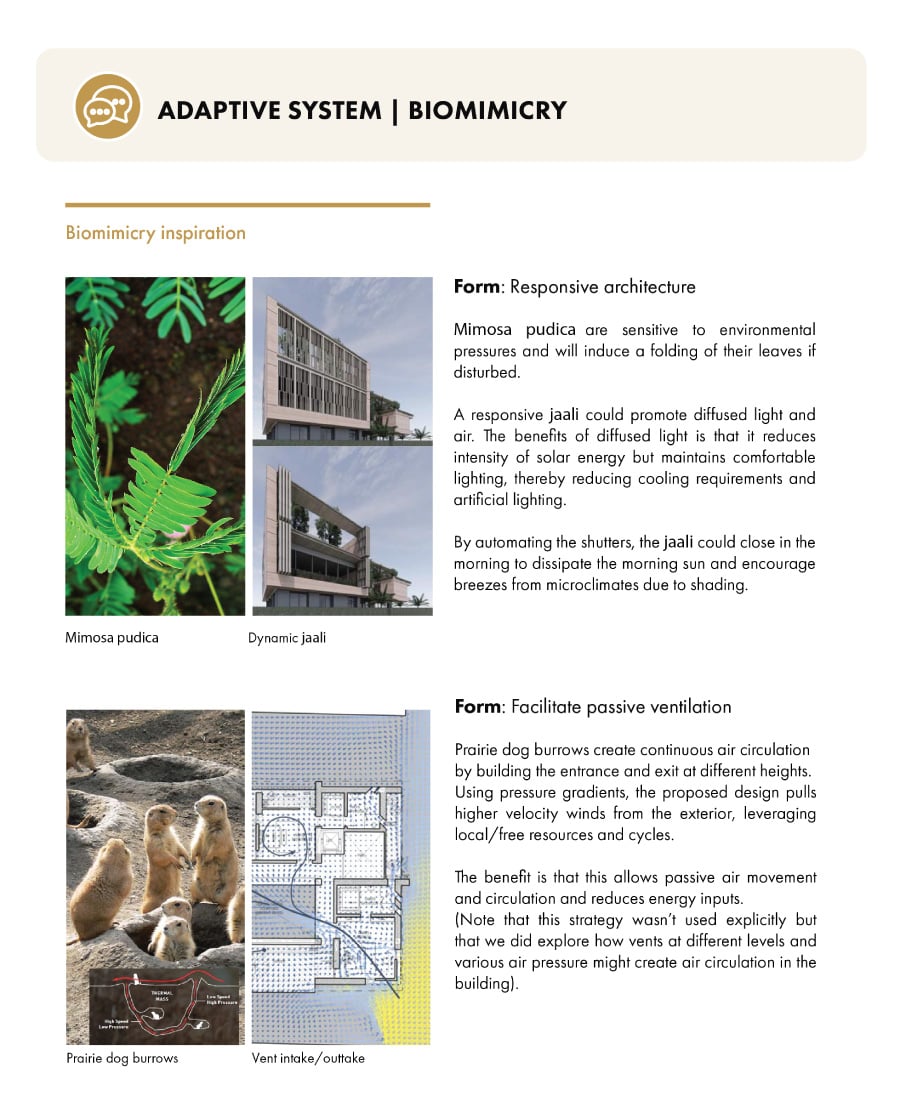

In a large residential building in India, we used the Living Story to help us better understand the local genius for solving some of the design challenges we were facing. This included organisms that could teach us self-cooling, water capture and storage, especially during monsoons and drought, and benign manufacturing strategies. We identified several other functions like we wanted the house to function like a forest, to provide self-sufficiency in terms of food and soil, and increase the biodiversity and blend the built and natural environments. In essence, we wanted to blur the building with a blend of nature.

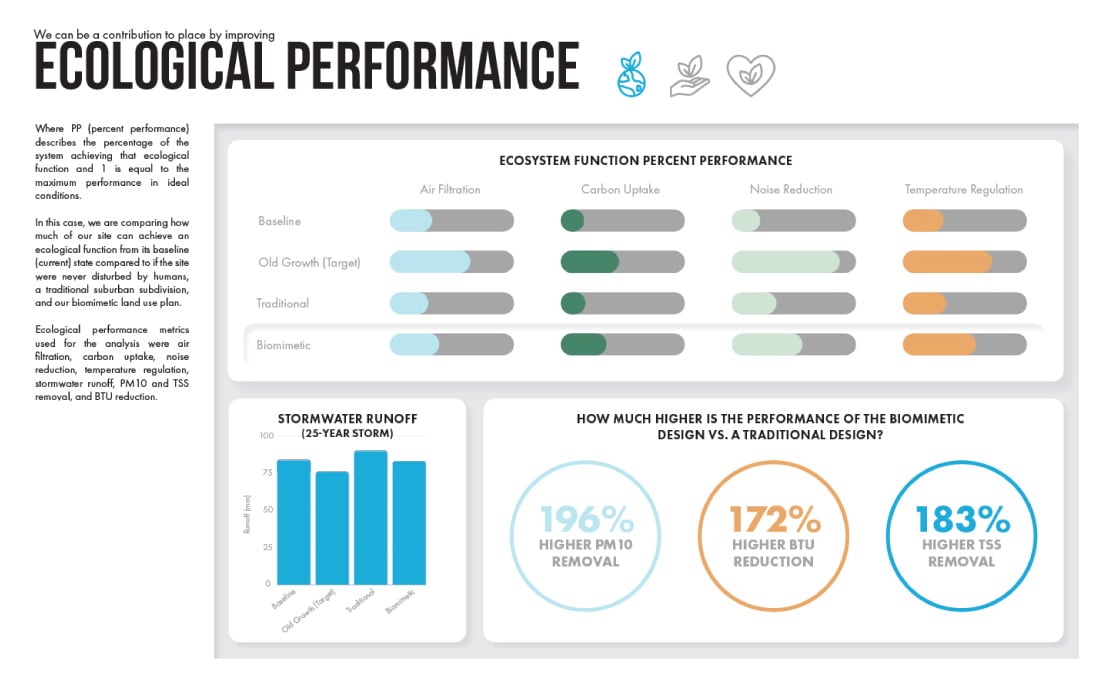

To begin, we looked to elephant skin and barrel cacti for cooling and found specific strategies that we could emulate in our design. We expanded our exploration to study organisms outside of our environment as well – looking at ant nests, termite mounds, and prairie dog holes to understand passive ventilation and air flow. We used permaculture for our food production, recognising that nature naturally creates symbiotic relationships between organisms to reduce material and energy inputs. In the end, we designed a house that improved the ecological performance of the site on all accounts, including carbon sequestration, air purification, 25-storm water retention, ambient temperature, noise reduction, NOx and SOx purification, along with decreased values of PM10.

We were able to prove the regenerative nature of our building and that its presence had greater ecological value than the site before.

Moving Beyond Less Harm

In each of these case studies, our Living Story formed the foundation for contextual designs that were resilient, creative, cost effective, and regenerative. We wanted to go beyond doing less harm and the belief that humans are an innately problematic species, which we are not. Like I said, our breath feeds trees, our bodies feed the soils. We are an integral part of our environment. We have just strayed in a destructive direction because of the assumptions we’ve been using to help us make sense of this complex and wild planet. But as Jenine Benyus, the woman who popularised the term biomimicry, said “we are not necessarily a bad species, but just a very young one” and the best way to live long-term in a place is to listen to the elders of that place.

Through the Living Story, we are trying to maximise that conversation. We are trying to build better by listening more effectively – learning what and who to listen to and what to listen for. However, doing this in a rural or more natural environment is very different from an urban one, which is where we are making a more concerted effort in our next iterations of Living Story. In these situations, our built environment has already dramatically changed the natural flows, ecosystems, and the trajectory of the place and so it is a bit of a unique story of a blended natural/built context.

However, this is also where we can have the biggest influence. Regardless of how urban a place may be, nature still wants to inevitably grow in, and into, it. Plus, we know through biophilia how helpful it is for humans to be reunited with nature again. In the India case study above, Stephane Lasserre from B+H Architects and I were exploring ways of brining mycelium into both the building materials of the space and the integration of nature into the design. We studied mycelium bricks (fireproof, nontoxic, insulating materials) and connected planters and sky gardens to mother earth through engineered shafts, allowing the mycelial connections to permeate throughout the building and back to the ground knowing that plants communicate through these networks and share resources as a source of resilience.

How can we leverage nature more strategically to encourage more life in our cities? How can we create spaces for emergent natural patterns, or to honour and encourage water to flow in more natural ways, to harness free energy and to design for cycles? What would it look like if we fought nature just a little bit less and designed infrastructure that could function more like a forest? In nature, trees pump water (without electricity), build solar collectors and manufacture materials. A forest is a place where waste does not exist and there is no unemployment. These systems have unique strategies to build resilience that we can learn from. For example, a tree canopy is designed in a way that creates a natural barrier for environmental pressures to come in and disrupt the undergrowth. An in-tact canopy is a natural wind and weather dissipative structure. But what else is out there?

There is so much we can learn from nature and biomimicry and the Living Story invite us to move beyond our more combative ways and extend beyond a goal of “doing less harm”.

We must learn to dance with nature in our designs but let nature lead.

At the root of our combative ways are our assumptions – the way we perceive nature and ourselves within it. What we know is that we can no longer build in ways that ignore the natural world. We know that we are intimately connected to it, we are a part of it, and without it, we would not survive. The unfortunate truth is that nature does not need us. We need nature. And so, we must design in a way that respects this relationship.