Chris McQuillan of B+H Architects discusses the six big lessons we have taken in our healthcare design due to the outbreaks of SARS and other infectious diseases.

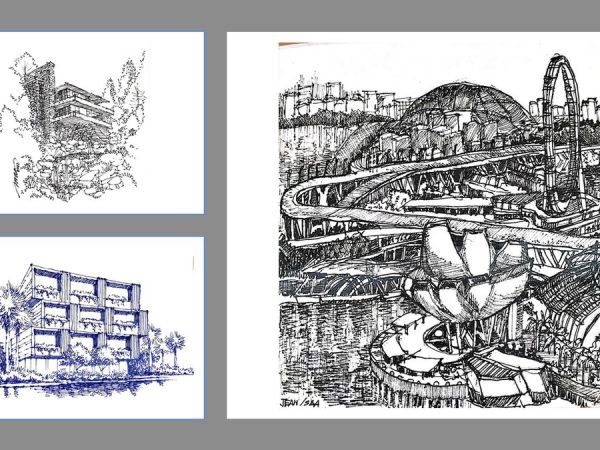

B+H’s Milton District Hospital project in Canada features isolated patient examination rooms

Our triumph over infectious diseases has redirected our focus to mitigating lifestyle ailments as their threats slipped from our consciousnesses – until now. In recent years, infectious diseases – chiefly SARS, MERS and H1N1, have transformed healthcare systems, facilities and the delivery of care around the world.

Hospital design has evolved in response and the lessons learned during these epidemics, particularly evident in those locales that were hardest hit by recent challenges, are proving important in helping our healthcare systems respond to Covid-19. Here are the essential innovations keeping us safer today:

1) Clean hands – infection studies have long shown that person-to person contact and physical contact with surfaces or through droplet spread, are common ways that microbes and viruses spread. Prior to the SARS pandemic, standards for hand-hygiene stations in hospital were inconsistent and often not applied. A key innovation was to codify a standard wherein every environment that involves patient-caregiver contact is equipped with a conveniently placed dedicated hand hygiene station (ideally a dedicated hand-washing sink, if not feasible an alcohol-based hand rub, also known as AHRB).

Decentralised nursing stations at Milton District Hospital, a B+H project, are located to support local access to patient data and to maintain clear view corridors to patients without needing to enter the room.

2) A clean environment – There is a new emphasis on the ability to decontaminate many, if not all, areas of the hospital. We now solely use non-porous materials with minimised/shallow joints and avoid shelves and recesses that are difficult to clean. We use technologies such as copper/ silver ion coatings and UV light sources to actively decolonise surfaces and entire rooms.

3) Isolation – Prior to SARS, hospitals had little physical infrastructure to isolate patients suffering from respiratory ailments. During the SARS crisis, many facilities constructed ad-hoc air handling systems or worked to re-balance building infrastructure to provide local or zoned isolation so that contaminated areas or individuals could be separated from uncontaminated areas. Subsequently, in all new hospitals, every department is equipped with isolation rooms (usually 5 to 10 percent of the spaces) and has the ability to separate zones of whole departments from the balance of the facility to give caregivers a variety of options to contain any infection.

Before SARS, the single bedrooms were reserved for those who could pay. To deal with pandemics, patient bedrooms have to be designed for isolation, as seen in Milton District Hospital, a B+H project.

4) Single bedrooms/ treatment bays – For anyone entering a hospital and wondering if it were designed before or after SARS, the clearest evidence is that the latter contains a far greater number of single and hard-wall enclosed treatment spaces and bedrooms. Before SARS, it was quite normal in emergency departments to separate most treatment bays with curtains. Single bedrooms were meant for those who could pay. It quickly became apparent that patient bedrooms and treatment areas needed to be designed and built to allow isolation.

The rooms can be negatively pressurised relative to the corridors. Thresholds provide ideal areas for protocols relating to the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Decentralised nursing stations are located for local access to patient data and to provide clear view corridors to patients without needing to enter the room. Today, virtually every bedroom, examination room and treatment area can be adapted for patient isolation.

5) Separation of flows – SARS and MERS presented unique challenges in managing the flows of patients and caregivers within the facility. Due to a heightened awareness of contaminated people and wastes, routes for patients and materials (particularly those associated with the treatment areas) were kept separate from other people and materials in the building. In many facilities, particularly older buildings, department floor areas often had a single point of access. The separation of flows – patients from supplies from public – was typically not prioritised, or postponed until after business hours.

In a pandemic scenario, these options are not available. More recent planning aims to maintain separate clean and soiled areas, to minimise the depth of ingress of dirty flows into departments, to place isolation spaces at departmental perimeters, to separate access for staff and materials from patients and families, and to provide a diversity of access so that portions of some departments can be independently accessed to treat different patient populations.

6) Access & Screening – Access points to healthcare facilities changed as we considered how to screen all people entering the buildings. Overall planning has responded with a clearer definition of a contiguous front-of-house ‘public zone’ now. Previously, the boundary between public and functional areas and access points was much less sharply defined. In addition, the footprint of access points increased, due to a need to accommodate screening stations and space to don and doff PPE.

Additional outdoor space is provided to allow the construction of temporary structures and services for purposes such as physical decontamination. All of these interventions allow our healthcare facilities far greater control over the status of people and materials entering and exiting.

The collective impact of these advances has readied us to handle far greater numbers of acute Covid-19 cases within our hospitals. We can safely separate staff and patients from each other and facilitate the turnover of spaces for successive waves of patients. While there are many other limiting factors relating to the sustainable level of pandemic care (including staff and supplies) our physical infrastructure is as ready as it has ever been.

The next lesson?

In the midst of this pandemic, we’ve all raised questions about how our healthcare facilities will need to change for a similar outbreak in the future.

The next frontier has been highlighted by our dependency on the ready availability of consumable supplies and key equipment (notably ventilators) to act as the first line of defence between caregivers and their patients. This is not a physical challenge but rather a logistical one. Healthcare already represents a high percentage of GDP in many advanced nations. Substantially investing in more healthcare infrastructure is likely to be unsustainable.

Our greatest opportunity to improve our response lies in harnessing other assets in our built environment. The lessons learned in effective hospital design can be applied to other buildings in our urban fabric, at various scales, to create a sustainable rapid response model at a local scale.

This is adapted from an article first published on the B+ H website here on April 17, 2020. The writer, Chris McQuillan ( B.Arch., FRAIC, OAA, LEED AP) is a Principal with B+H Architects and based in Toronto.

The experience of B+H in healthcare design

For over 50 years, B+H Architects, a member of the Surbana Jurong Group, have been providing progressive healthcare designs for projects around the world. These include:

- Changi General Hospital (Integrated Building) | Singapore | 61,000 sqm | Completed 2015

- Changi General Hospital (Medical Centre) | Singapore | 42,000 sqm | Completed 2017

- National University Centre for Oral Health | Singapore | 39,000 sqm | Completed 2018

- SGH Outram Community Hospital | Singapore | 100,000 sqm | Completed 2019

- Department of Emergency Medicine Building at SGH | Singapore | 58,000 sqm | Under Construction

- Gleneagles Medini Hospital | Iskandar, Malaysia | 130,064 sqm | Completed 2015

- Columbia Jiaxing Hospital | Zhejiang, China | 100,292 sqm | Under Construction

- Milton District Hospital Redevelopment | Milton, Canada | 30,658 sqm | Completed 2017

- Markham Stouffville Hospital Redevelopment | Markham, Canada | 47,000 sqm | Completed 2014

- St. Catharines Hospital & Walker Family Cancer Centre | St. Catharines, Canada | 89,187 sqm | Completed 2012

- Sickkids Hospital – Patient Support Centre | Toronto, Canada | 42,000 sqm | In Progress

- Michael Garron Hospital – New Patient Care Tower | Toronto, Canada | 59,500 sqm | In Progress

- Corner Brook Health Centre | Corner Brook, Canada | 60,900 sqm | In Progress

The site of the Changi General Hospital (Integrated Building) in Singapore