Menu

SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL

Shaping cities at human scale helps people stay

healthy and socially connected

Constant social interaction, for play and discovery in a community, is vital for mental and physical health.

Abstract: The rise of the Industrial Revolution has ushered in not just progress, but also a sense of

chronic social isolation and loneliness, which has the same impact as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Bucking this trend is the Roseto Effect, first noticed in a small Pennsylvanian town from 1954 to

1961, where heart attacks were fewer compared with the rest of America, and where people lived

longer. The correlation between health and strong social connections is also apparent in other

societies. Researchers believe that when the city grows to a level beyond the human scale, people

cannot relate positively to one another. But if the growth of cities is managed at a more granular

level, the Roseto Effect could potentially be recreated for city-dwellers. Designing cities with better

walkability and wayfinding, incidental spaces with small pocket parks and urban farms are some

effective ways to encourage a sense of belonging among the community.

COMMUNITY COHESION AND LONGEVITY

In Roseto, a small town in Pennsylvania, USA, an unusual phenomenon was observed in the 60s.

There was an unusually low rate of myocardial infarction in this Italian-American community compared

with the typical American town. From 1954 to 1961, Roseto had nearly no heart attacks for the

otherwise high-risk group of men 55 to 64, and men over 65 had a death rate half of the national

average. Researchers attributed their good health to strong community cohesion and lower stress –

the Roseto Effect.

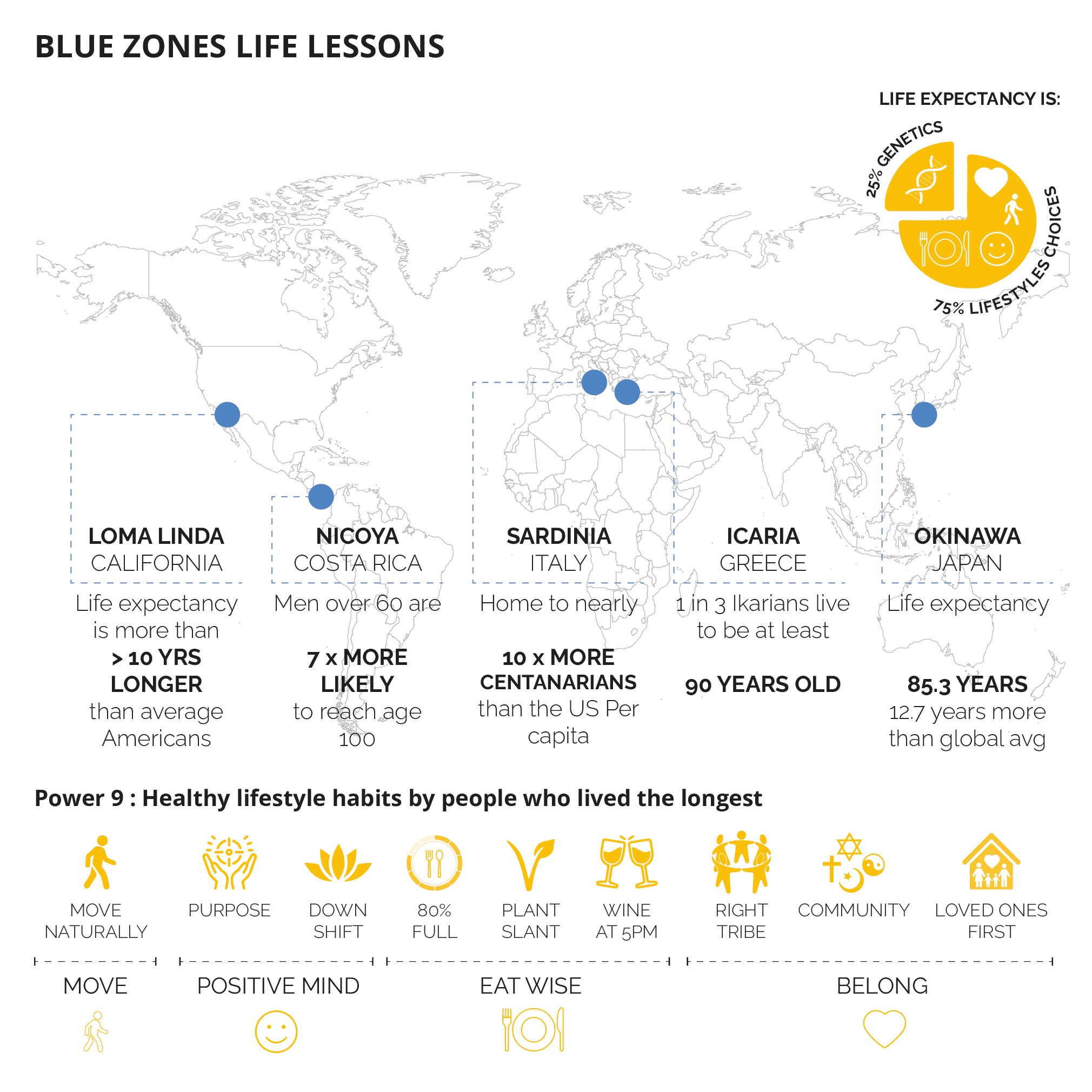

Drawing nine lessons from the world’s Blue Zones on living a long, healthy life (Information source: World Economic Forum.) (Graphic by: Wong Lei-Ya)

This is but one of the studies that corroborate what is commonly found in Blue Zones Longevity

Hotspots around the world – that community life, friendships and strong families add years of good

quality life to people. In Okinawa (one of the five Blue Zones), a startling 68 in every 100,000

persons is a centenarian, whereas the world average is 6 per 100,000. Dr Bradley Willcox, a

member of the Okinawa Centenarian Study research team discovered that socialising is one of the

reasons many Okinawans live healthily to 100 and older.

While it is logical to band together for strength in numbers in the early hunter-gatherer stage of

homo sapiens, the benefits of social interaction might have also worked its way into our system and

reaped health benefits.

In a Harvard study which tracked the health of 268 Harvard sophomores in 1938 during the Great

Depression for 80 years as part of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, evidence pointed to the

strong relationship between human relationships and physical and mental health, surpassing

predisposed qualities such as genetics and early life circumstances.

Sadly, the Roseto Effect came to an end in the early 70s. As the residents gradually abandoned the

socially cohesive culture and adopted the typical suburban lifestyle of small families, long stressful

work hours and social isolation, the rate of men under the age of 65 having heart failures

sharply increased.

A global chronic condition – loneliness, especially amongst the elderly, is exacerbated by social isolation. (Photo: Debbie Loo

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/projects/2013/high-rise/your-stories/index.html?section=balconies&slide=1229)

Even as mounting evidence proves that our health is affected by our social networks, this

connection, which has likely evolved over many millennia, is being threatened by a highly disruptive

age – the Industrial Revolution. Since its arrival in the 19th century, social isolation has been

observed to infect industrialising nations. The rapid advancement of technology and the even more

recent internet era have ushered in a global chronic condition: Loneliness

Today, our lives are lived increasingly online, rather than among real persons, and the damage

done to our health and wellness further intensifies. It has been estimated that the health impact of

chronic social isolation is as bad as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. In a Duke-NUS Medical School

(Singapore) study it is found that loneliness can shorten life expectancy by at least three years.

WHY IS LONELINESS GROWING?

The industrial revolution helped to create modern lifestyles and cities, which were frequently portrayed

as inherently anti-social or even ‘evil’. Observing the harsh realities of their day, writers from

Dostoyevsky to Dickens represented the city as a place of alienation, where “materialism hardened the

heart and diminished compassion, altering our sense of human scale, our sense of community”.

Across the globe, rapid global urbanisation is happening right now, with more than two-thirds of the

world’s population estimated to live in urban areas by 2050. Cities are very powerful forces that

significantly influence the quality of lives, because of the captive nature of the experience lived by

all residents in a city. No one can ‘opt out’ and avoid being subjected to the perpetual effects of how

the city is planned.

Just as we need intimacy with people to form relationships, we need the right urban scale to relate

well to our environments. Urban scale describes the sense of height, bulk, and overall architectural

articulation of a place or individual building – often in relation to the size of a human body.

When the city grows to a level beyond the ‘human scale’, the individual loses the ability to relate

positively to the place he or she lives in. Urban designers understand that, beyond four storeys, the

human senses are unable to perceive social activities on the streets anymore. There is a

relationship between scale and the quality of social life.

While much has been said about how our health is influenced by social interaction, more can be

said about how social interaction is influenced by the scale of our environment. Urbanisation is not

the problem, but urban growth at a wrong scale can obliterate any attempt for social life to thrive.

Rather than resisting urbanisation, it would be more tactical to ‘granularise’ growth in the right scale.

We explore three approaches to a ‘scaled growth’ of cities.

RIGHT-SCALING FOR COMMUNITY

Different scales of urban environment creates different social orders. A large-scale city environment

favours less socially-conducive living, while a town-block scale environment encourages greater social

engagement. Roseto was re-created in Pennsylvania based on the original mining town in Italy, starting

from 1882 after twelve pioneering immigrants moved to the United States for better mining opportunities.

The intimate human scale of the town was also re-created with streets names and landmarks such as

churches in the same manner.

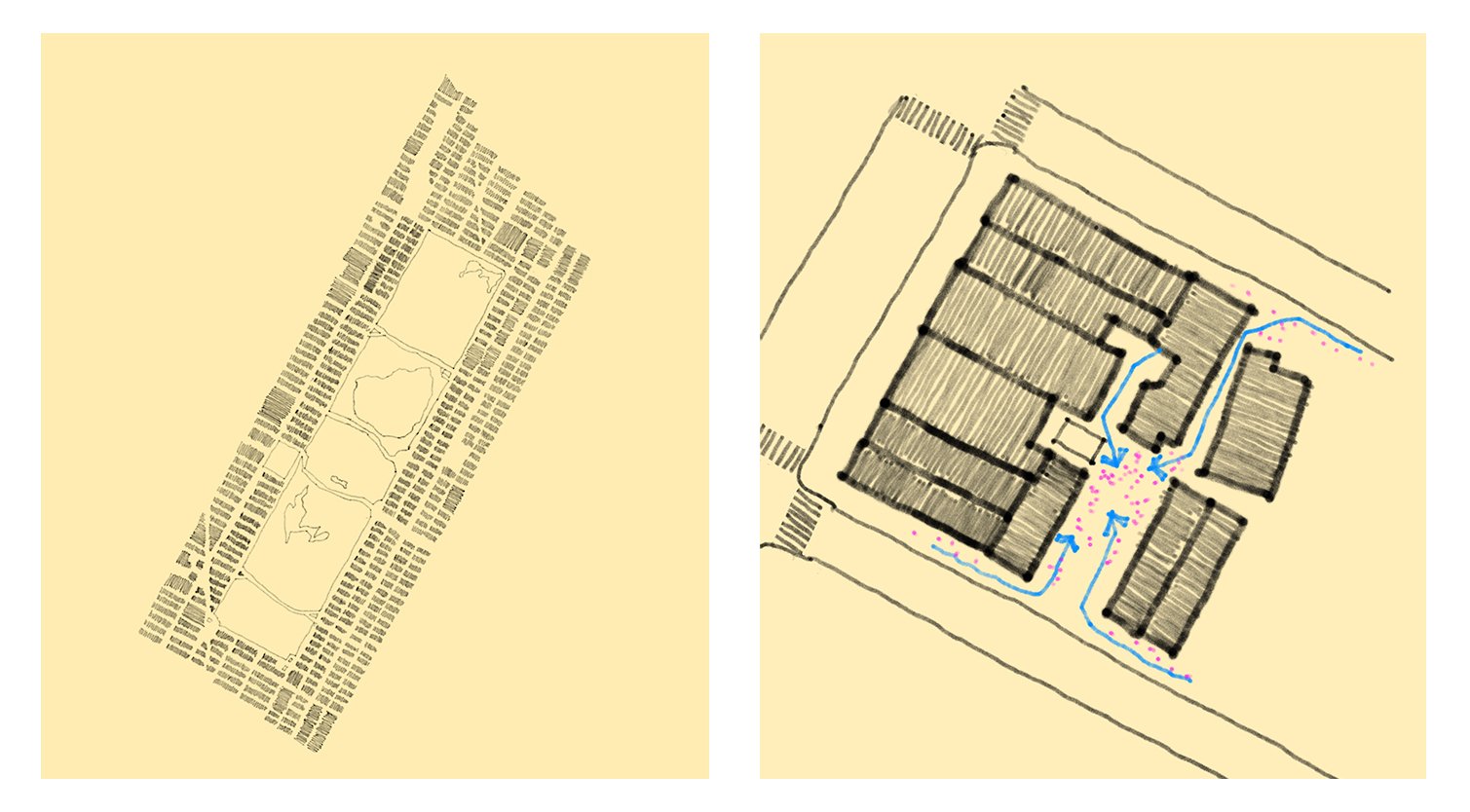

Central Park (left) versus Paley Park (right), Manhattan. Enclave-scale public spaces encourage communities to form more effectively due to the intimacy and

familiarity afforded to the users. (Image: Michael Leong)

Pocket parks are good for getting to know the other users who tend to be regulars from the

neighbourhood, thus creating a sense of belonging and ‘shared privacy’. Whereas a large open field

makes it hard to relate oneself, and most likely remain as a wasted green space as it does not

attract ad hoc users to inject life. Urban squares such as the People’s Park in Eu Tong Sen Street in Singapore is

an optimally sized public space that strikes a balance between a sense of enclosure and porosity.

Community and familiarity happens informally when people can encounter each other in right-scaled spaces like civic squares and town plazas.

(Source: https://jthejon.blogspot.com/2015/08/hawker-hopping-peoples-park-complex.html)

Urban farming is a highly beneficial social activity which will generate hours from a shared passion.

It works best when the plot is part of the open landscape around a residential estate, with a strong

visual association between the two. People can freely access the plots and groups can work on the

crops together at any time. However, we often see these well-intended plots being fenced up in

housing estates, from a fear of vandalism and theft. Instead of a community pride, they often

become an urban blight of imprisoned vegetables. If the residential estates are correctly scaled to

facilitate a sense of ownership and surveillance, fencing up the plots would be unnecessary.

At the right scale, the human mind can build up a strong sense of familiarity with their surroundings.

Wayfinding is much easier as urban elements such as shopfronts, markets, street furniture and

most of all, familiar faces, all contribute to ease of free navigation.

RIGHT-SCALING FOR mobility

How does a community move around every day? Commuting is an inevitable aspect of city-living,

and a major part of life for all city dwellers. A city-block scale requires longer commutes to cover the

distances needed to reach further destinations, compared to the shorter commutes needed for

town-block scale districts. With larger city-block scales, one will need to cover longer distances to

reach the next block. Town-block scale districts, in comparison, has shorter distances between each

block and oftentimes offer avenues for shortcuts, that larger city blocks with impermeable elevations,

often do not provide.

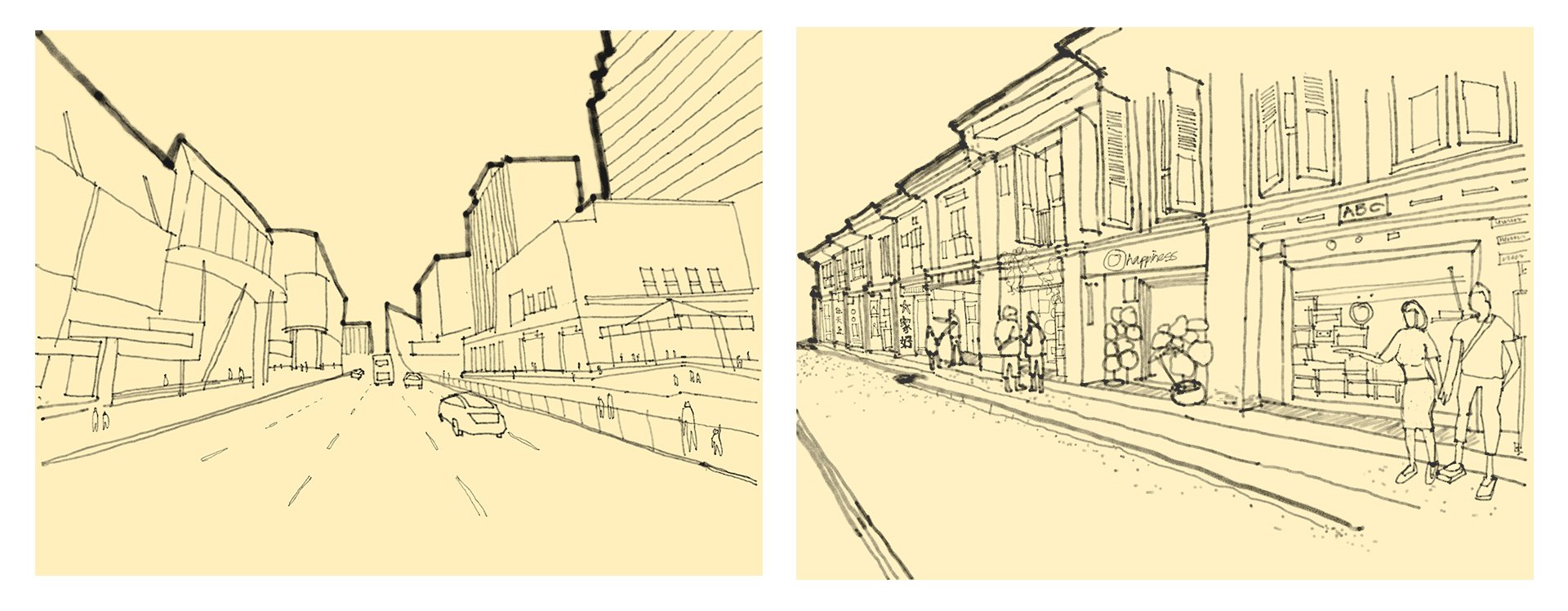

Orchard Road (left) versus Haji Lane (right), Singapore. City-scale blocks are better appreciated by fast-moving motorists while shophouse-scale blocks can

be slowly taken in by pedestrians on foot. (Image: Michael Leong)

In addition, increased opportunities for pedestrian movement encourages walkability, which improves

the well-being of the commuter.

When it is too far to walk, people will just rely on vehicles.

In the 2040 Land Transport Master Plan, the Land Transport Authority of Singapore has set out to

achieve a “45-min city, 20-minute towns” target, in a bid to cut down commuting time for residents in

Singapore. One of the key recommendations of the Master Plan is – Healthy Lives – Safer Journeys

– which aims to dedicate “more spaces for public transport, active mobility and community uses”.

In Okinawa, a traditional saying goes “Live far enough away from your family so you’re not running

into them every day, but close enough to take them a warm bowl of soup – on foot.” This age-old

practice guided the scale of the communities in the sub-tropical island, making sure friends and

families are still within easy reach, while keeping visiting folks active and healthy at the same time.

By designing the streets for the average walking speed of 1m per second, we enhance the walkability of the urban environment. In fact, people would prefer to walk rather than to drive if the streetscape is designed in such a way that permits them a sense of discovery and connection. Large city-scale blocks are better appreciated by fast-moving motorists while shophouse-scale blocks can be slowly taken in by pedestrians on foot. A city that is designed for driving may be a more expedient way to urbanise, but it will never have the endearment and sustainability of a 1m-per-second city.

Similarly, community spaces work best in a 1m-per-second city. Only at a human scale will such

community spaces be regularly filled up with social activities, because it removes deterrents such

as finding a parking space, long stretches of polluted kerbside walkways or simply getting lost.

RIGHT-SCALING FOR SUSTAINABILITY

Population Health and sustainable developments are also symbiotic. One of the greatest ironies of

healthcare facilities is that being one of the most energy-intensive building typologies, they contribute

substantially to the pollution and climate change in the world. These in turn deliver a negative impact to

the very population that it is trying to help. Policy-makers and healthcare operators are wary of an

indiscreet use on tertiary care and are working towards re-distributing care where they are best

provided. While hospitals are designed for illness, cities must be designed for wellness.

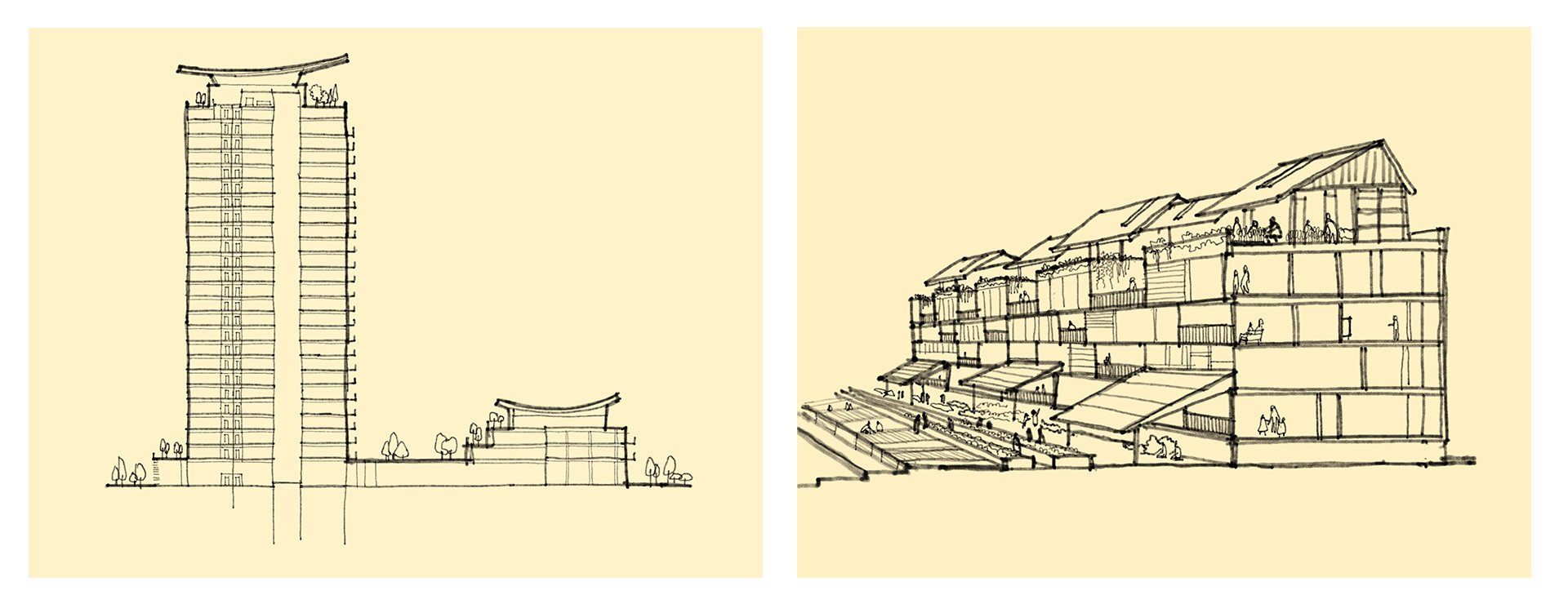

Residential tower (left) versus low-rise apartment (right). Human-scaled developments are more conducive for a socially-cohesive culture and sustainable

outcome. (Image: Michael Leong)

As building blocks of any city, residential enclaves can potentially form a sustainable web of a

healthy population. One approach is to develop enclaves centred on sustainability itself. The

phenomenon of Ecovillages has started to sprout around the world. According to Global Ecovillage

Network, these are traditional or urban communities that develop according to the four dimensions

of sustainability – social, culture, ecology and economy.

The “As One Suzuka Community” – an urban eco-community established in 2001. (Photo with permission: The As One Suzuka Community.)

A daily dose of chess – forming strong bonds on sidewalks, stimulating the

mind for a joyful health (Photo: Wong Lei-Ya)

Ecovillages advocate the high quality, low

impact lifestyles that hinge on restoring the

environments, giving back more than taking

from it. The philosophy of the eco-villagers leads

them to adopt small-scale lifestyle changes such

as growing healthy food, recycling, and using

renewable resources. Noticeably, there is also

often an element of sharing and reaching out to

neighbours in need. Ecovillages are correctly-scaled communities with a

democratic social order.

In the context of everyday life, having a shared

game of chess in the neighbourhood or a daily

taiji session among neighbours are examples of

small but powerful ways to stay connected while improving a

sense of well-being.

A daily dose of chess – forming strong bonds on sidewalks, stimulating the

mind for a joyful health (Photo: Wong Lei-Ya)

Ecovillages advocate the high quality, low

impact lifestyles that hinge on restoring the

environments, giving back more than taking

from it. The philosophy of the eco-villagers leads

them to adopt small-scale lifestyle changes such

as growing healthy food, recycling, and using

renewable resources. Noticeably, there is also

often an element of sharing and reaching out to

neighbours in need. Ecovillages are correctly-scaled communities with a

democratic social order.

In the context of everyday life, having a shared

game of chess in the neighbourhood or a daily

taiji session among neighbours are examples of

small but powerful ways to stay connected while improving a

sense of well-being.

A ground-up and multi-racial community Taiji group at Bishan Community Centre: Bringing people back to participate in public life in civic squares can help

rebuild resilience in society. (Photo: Debbie Loo)

TOWARDS A NEW ROSETO

With awareness and concerted efforts, we can resurrect the Roseto effect even in modern high-density

developments. In Tirana Riverside, Albania, Stephano Boeri Architects imagined a 29-hectare

Masterplan made of interconnected and self-sufficient small communities. Originally designed to

respond to the new norms of the pandemic, the intention of cutting down travelling which aggravates

infection, will collaterally create inter-connected and resilient communities.

Thinking and planning at the right urban scale sets the city up for a sustainable and resilient

community, which is the critical foundation of a healthy population. To be sure, many factors need to

align, such as the cultural, social and economic environment, just as the ideal context that Roseto

used to be in. Masterplanners and architects can certainly design the city of the future as a living lab

for new Rosetos to be cultivated.

The SEEDS Journal, started by the architectural teams across the Surbana Jurong Group in Feb 2021, is a

platform for sharing their perspectives on all things architectural. SEEDS epitomises the desire of the Surbana

Jurong Group to Enrich, Engage, Discover and Share ideas among the Group’s architects in 40 countries, covering

North Asia, ASEAN, Middle East, Australia and New Zealand, the Pacific region, the United States and Canada.

Articles at a glance